|

|

Historically, the Willapa Bay has been the home of three culinary oyster species: the Olympia oyster (Ostrea lurida or O. conchaphila), the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) and, since the early 20th century, the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas). The Willapa Bay got off to a late start in terms of "oyster history". Up until 1850, only Native Americans indulged in the shellfish bounty of the bay. During the Gold Rush years, the native Olympia Oyster became the claim to fame of the magnificent Willapa Bay. Literally billions of individuals of this species were harvested between 1853 and the 1900. A few years after 1900, this species no longer existed in commercial quantities. Merely a few Olympia oysters can still be found in Willapa Bay today. In the 1890s, the Eastern Oyster was introduced on a large scale. Cultivation of the Eastern Oyster proved to be problematic and expensive. The commercial success with this species varied from year to year. In 1919, for some unexplained reason, most of them died and brought the cultivation to an abrupt end in the early 20s. A new species, the Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas; back then called the "Japanese Oyster"), was introduced in the late 1920s. Today, the Pacific Oysters rules Willapa Bay's entire oyster production. Willapa Bay Historical Harvesting Methods:

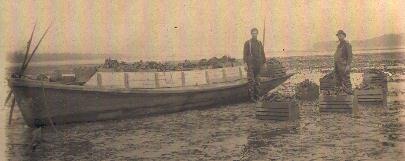

Olympia Oyster For most of the second half of the 19th century, the Willapa Bay was called "Shoalwater Bay". Enormous quantities of Olympia Oysters existed in the tidal and subtidal zones. They were often called "Shoalies". Initially any kind of floating craft would do for harvesting purposes. Indian dugout canoes, log rafts and simple dinghy designs served the purpose. Later, oystermen would take to a flat bottomed boat design they called a "bateau" (simply the French word for "boat"). These bateaus (or "bateaux") measured about 30 feet in length with a carrying capacity of about 70 bushels of oysters. Early on, it was generally a matter of "being in the right place at the right tide". Oystermen would anticipate the low tide and navigate their vessels to a promising oystering spot in the bay. The receding water left the spot (and the boat) high and dry. Oystermen could then proceed to drudge though the exposed muddy tideflats and pick the oysters up by hand. The incoming tide would then conveniently float the boat with its heavy cargo of oysters. The oystermen would then return to shore and process their catch. Another way to find Shoalies was to navigate the vast mosaic of shallow canals left in the bay at low tide, as Olympia oysters often lined these canals.  Image above: Early 20th century photograph of two Willapa Bay oystermen and their bateau. These oystermen obviously worked hard and fast collecting oysters. The bateau seems filled almost beyond capacity. The photograph was likely taken in the later part of the 1930s, which would evidence tremendous natural propagation of the Pacific oysters (introduced on Willapa Bay in the late 1920s). The tides granted these men only a few hours during the outgoing, slack, and incoming tide. Oystermen who work the exposed tideflats on foot are refered to as "pickers". Click image to enlarge. Tonging ultimately established itself as the most common method of harvesting. This method of harvesting allows an oysterman to be somewhat independent of the tides and work submerged oyster beds. Oystermen would operate two long wooden poles joined by an iron pin, which in turn operated a pair of interlocking rake-like ends - much like a pair of scissors or pliers. Decking, about two feet wide, ran along the inside of both sides of these tonging bateaus. The oystermen would balance themselves on these narrow strips of decking and operate their tongs. If the bateau was sitting on the tideflat at low tide, the decking could also serve as a place to temprarily deposit bushel baskets or crates full of oysters out of the mud (see image above). The inside margins of the decking were edged vertically by boards, rising about a foot above the decking. These boards would form a large, square holding area where the harvested oysters were stored. Oyster tongs were not a novel invention. They had been in common use on the East Coast and Europe since the 18th century. Although oyster tongs are simplistic tools by design, operating them effectively requires great skill. Working these tongs for hours on end is physically extremely taxing. The early oystermen of the Northwest often had to work in miserable weather conditions. All the job actually had going for it was good pay - provided of course enough oysters had been harvested after a long, hard day. This became a real problem by the end of the 1880s. Olympia oysters were getting increasingly tough to find in Willapa Bay. By the early decades of the 20th century, commercial quantities of the Olympia Oyster ceased to exist. The ranks of the Willapa Bay oystermen thinned greatly. Willapa Historical Cultivation Methods:

Eastern Oyster After the completion of the transcontinental

railroad in 1869, California oystermen started bedding Eastern

oysters successfully. Countless rail cars full of young oysters

were shipped from the East Coast to California. Although shipping

oysters by rail was very costly, the San Francisco market was

ready to pay almost any price for true Eastern oysters. Despite all the setbacks, a number of Willapa Bay oystermen remained undaunted in their cultivation efforts and managed to bring limited commercial quantities to market. The cost of importing the Eastern oysters by rail continued to climb. Willapa Bay oystermen made the best of it up until 1919, when an unexplained natural phenomenon killed almost all the Eastern oysters in the bay. By the early 20s, the Eastern Oyster had proven itself far more trouble than it was worth. The cultivation ended. Later in that same decade, a new species, the Pacific oyster, was successfully introduced. Interesting note: Today, limited quantities of Eastern oysters are cultivated again in Washington State waters with oyster seed stock from local shellfish laboratories. I've tried many and must say that I found their taste and texture to be truly superb. It must also be noted that excellent Olympia oysters are also cultivated in commercial quantities in Puget Sound (around Totten Inlet).

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|